Four Tips for Memorizing Vocabulary

...with a second worksheet from Isidore of Seville's Etymologiae

Have you ever encountered a word that just won’t stick? Maybe you’ve written it on Post-Its and fixed it on every surface in your apartment? Perhaps you’ve recorded and listened to it on repeat on your SmartPhone? And, geez! You’re constantly looking it up a dictionary when you encounter it! Why, oh why, won’t it stick?

Research shows that vocabulary acquisition is best achieved through spaced repetition. Sure, cramming for a language exam may be effective in the short-term, but have you really memorized those words for the long haul?

One theory around memorization emphasizes time, ensuring that there’s not only contextual variance in your encounters with certain words, but also temporal variance (Kang, 2016: 14). While I previously defended the “brute-force” approach of rote memorization (because, yes, it does work to a degree!) this post will discuss how to marry short-term memorization strategies with approaches aimed at achieving long-term learning gains.

Learning vocabulary can be hard.

The struggle can be real, friends. Sometimes there’s no rhyme or reason why some words stick and others don’t, but for the latter circumstance, one theory holds that we may not be establishing sufficient linkages between words and their meanings. An older study from the 1970s found that meaning recall rested on four strategies:

(1) Repetition based on a verbal rehearsal of the word and its meaning;

(2) Reading sentences containing the word;

(3) Generating one’s own sentences using the target word; and

(4) Seeing an image of the target word (Bower & Winzenz, 1970).

Admittedly, my own adherence to these modalities has been inconsistent, though variations of these four recommendations have found themselves reflected in various language textbooks. For example, I first encountered a variation of #4 in Carole Hough and John Corbett’s Beginning Old English where they recommended using diagrams to express topical relationships between words like social hierarchy, family structures or physical distance. I certainly spent some time drawing maps and pictures with verbs and prepositions of motion, vocabulary focused on natural phenomena, and even professions, but these diagrams did not necessarily enhance memory recall absent other contextual cues.

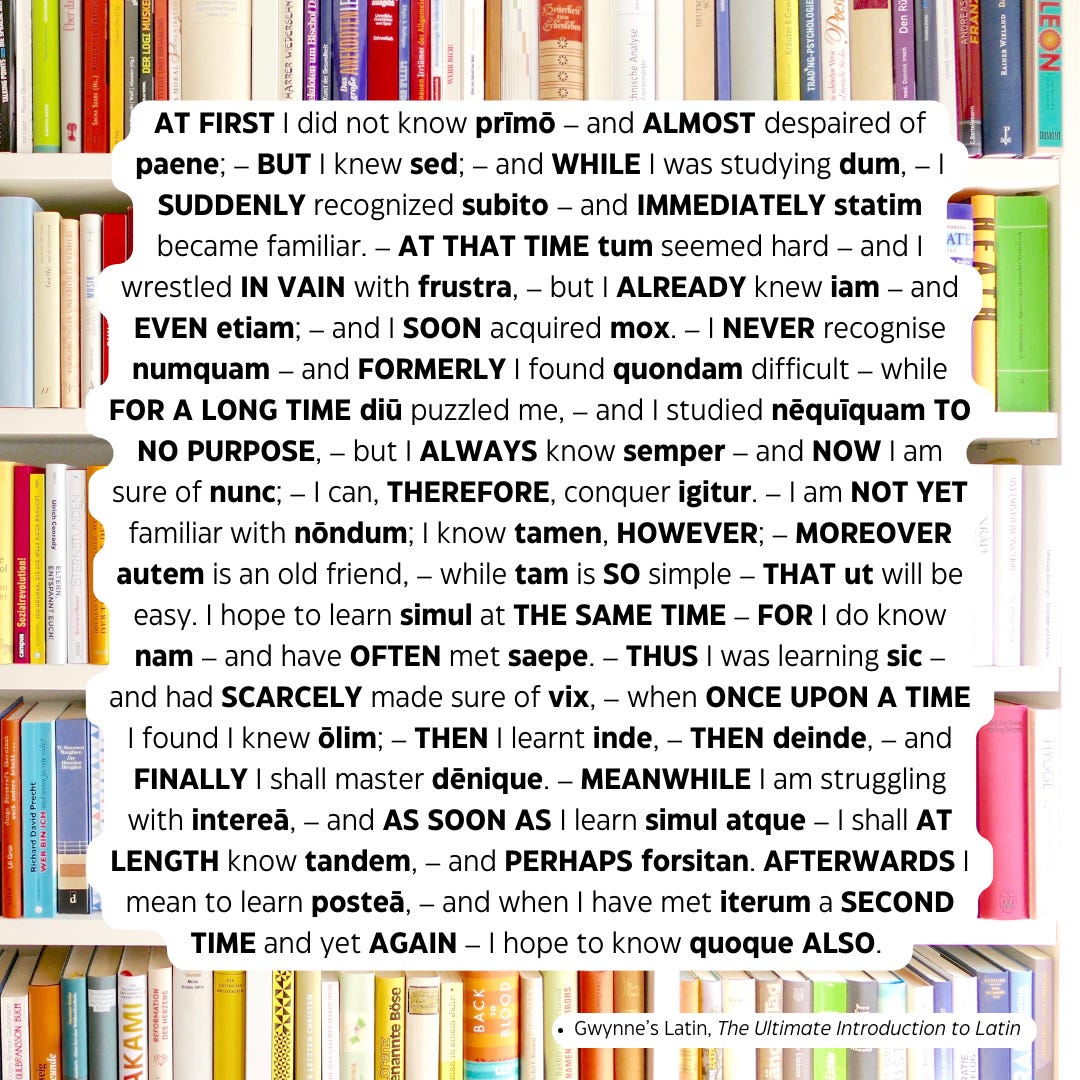

In order to be successful, it seems the “science” has spoken: you need to vary the encounters, adding your own generated sentences, finding sentences that contain the word(s), and regularly rehearsing their meaning to more successfully internalize vocabulary. I came across an interesting passage in Gwynne’s Latin Grammar, which offered a clever way to learn adverbs and other “little words” that can sometimes consume early-stage language acquisition. It made me think that creating something similar—adding a combination of English definitions with your target-language word(s)—may be worthwhile, especially if creating full sentences in your target language seems daunting.

Ultimately, the key to longer-term retention is what scholars have termed “deep processing.” To put it simply, there’s a hierarchy of efficacious learning. For example, word lists are fine, but those same words encountered in sentences are better because they require “semantic elaboration”—a fancy term for the word and its meaning to be more effectively internalized and later retrieved (Baddeley & Hitch, 1997: 25). The depth of learning is what consolidates memory recall.

Varying exposure is key.

An interesting point raised about learning so-called “dead languages” is the limited modal exposure outside the “classroom.” Whether that’s a literal, virtual or individual environment dedicated to language learning, the point is that nobody orders their peppermint mochas in West Saxon.

Scholars have also remarked on the low-level stakes involved in studying these languages: without the same timing pressures forcing memory recall, reading and translation can lead to increased floundering. Add to this the typical emphasis on grammar and translation rather than reading for comprehension and we ultimately arrive at a scenario where we have little pressure placed on retrieving words.

Nevertheless, there are potential tools that can force you to raise the stakes. There’s, of course, the classic timer—a dreaded tool that I often use, taking a paragraph, an old-school paperback dictionary and a pencil to a Latin text to see how much I can understand and translate within a thirty- or sixty-minute window. (And I stress that there’s difference between “understanding”—an arguably rough exercise to arrive at the gist of the text—and “translation”—being an accurate rendering of the original text into English.) But, there’s also the under-emphasized sentence generation mentioned above in strategy #3.

For years, I refused to attempt composing my own sentences in Latin, mostly because a single sentence could take me upwards of ten minutes to produce. Watching my brain slowly creak through the sequence of subject, verb, object, adjective, and inflection felt like a form of intellectual torture that I simply declined to subject myself to until I realized that I wasn’t making significant vocabulary gains after hitting an intermediate level. Biting the bullet, I began writing a painfully boring story about my cats and their daily adventures. You can write about your daily adventures, make up a fictional character or engage in whatever Tolkienesque world-building floats your boat, but the point is to begin using those target words in sentences. You may not have an entirely syntactically or grammatically correct sentence, but taking your brain through the mechanisms of memory recall in the opposite direction can be valuable.

Assembling your contextual tools.

Textbooks like the beloved Lingua Latina per se illustrata that promote vocabulary and grammar acquisition through comprehensible input can be effective for early-stage tools. A core set of words in different forms consistently encountered aid in longer-term retention. As a beginner in Latin, for example, the Internet is replete with free resources, including videos that read LLPSI or the Cambridge Latin Course aloud thereby increasing the input sources for a range of core vocabulary.

Intermediate learners seeking accessible original texts that are beyond LLPSI, but perhaps several steps below Cicero may struggle to find comparable resources, especially ones glossed by a modern editor. If your interest runs to Medieval Latin, options are fewer, though scholars such as C.T. Hadavas and Geoffrey Steadman are filling this gap. However, if your interests veer away from the Vulgate, Geoffrey of Monmouth or the Gesta romanorum, then you may need to create your own resources.

Medieval works are often highly derivative with whole passages adapted or copied verbatim from other sources. For example, the natural philosophical and cosmological works of Isidore and Bede owed their intellectual debt to Pliny, while Ælfric’s homilies see echoes of Bede, Augustine and Pope Gregory the Great. If you know something about the intellectual influences of the author whom you’re reading, then consulting those influences and identifying the passages on which these texts were based could help you amass a small corpus of texts that you can vary in your practice to achieve contextual variety.

Once you’ve assembled your sources, ensure that you’re reading them frequently and aloud. Studies of modern second language learning have shown that reading aloud can increase comprehension, particularly when learners are attempting to interpret content. Intonation, association and speed have all been noted as positive benefits to reading aloud. Verbal repetition of target vocabulary can also take place as you substitute the English definition for the word you are aiming to memorize, or simply reciting it after reading it in a sentence.

Finally, be sure to generate your own sentences if you are able. Try summarizing the passage you read in your target language, using the word(s) that you are trying to memorize. Given the emphasis I’ve placed in this article on sentence generation, in the worksheet for the second installment of Isidore of Seville’s On Portents, one activity is entirely focused on making your own sentences from an available word list. These sentences can be a combination of English and Latin, entirely in Latin, or simply using the word provided in an English sentence—it doesn’t matter. The goal is to add to repetition, reading and rehearsal through generation.

Isidore’s Etymologies continued.

Following the previous post on portents (portenta), this reading unpacks the next few paragraphs, focusing on portent-like beings (portentuosa). In these excerpts, we are introduced to variances in appearance occurring at birth, as well as physical mutations that are atypical and, in some instances, have their origins in myths and historical accounts.

Mary Beagon, writing on “human” and “human-instigated anomalies” in Isidore and Pliny, argues that the definition of portents encountered in the previous reading carefully distinguishes between “anomolous portenta, ostenta, prodigia”—fleeting divine indicators—and people born with portent-like qualities (Beagon, 2016). Though they still occupy “the parameters of the acceptably natural,” it is clear that they are different in some way, whether in size—as in the case of Tityos or the pygmies—or in physical characteristics: think swapped organs, extra body parts or eyes in one’s chest or forehead (oculos in pectore vel in fronte).

In this worksheet, there’s a grammatical section on alius, alia, aliud vs. alter/alter given the frequency with which it appears in this excerpt. In the spirit of memorization practice, two blank tables are provided to allow the drilling of alius, alia, aliud from memory. A section on vocabulary building with respect to the parts of the face allows us to tackle the nitty-gritty of eyebrows, temples and cheeks, going beyond the caput and the os. Finally, some English-language prompts are provided to practice sentence generation, although you’re welcome to devise your own.

As always, I apologize for any mistakes. If you catch any and want to point them out, write me at studieslatin@gmail.com so I can correct and reissue these worksheets. Ultimately, I hope that their lack of perfection don’t preclude their utility!

Bibliography

Baddeley, Alan D., and Graham J. Hitch. "Is the levels of processing effect language-limited?." Journal of Memory and Language 92 (2017): 1-13.

Beagon, Mary. "Variations on a Theme: Isidore and Pliny on Human and Human-Instigated Anomaly." Isidore of Seville and His Reception in the Early Middle Ages: Transmitting and Transforming Knowledge, ed. Andrew Fear and Jamie Wood (Amsterdam, 2016): 57-74.

Bower, Gordon H., and David Winzenz. "Comparison of associative learning strategies." Psychonomic science 20.2 (1970): 119-120.

Kang, Sean HK. "Spaced repetition promotes efficient and effective learning: Policy implications for instruction." Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences 3.1 (2016): 12-19.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to dead language autodidact to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.