Learn the German of the Middle Ages!

An In-Depth Interview with Substack Author Robert Whitley

In this month’s language-learning post, Robert Whitley, author of an eponymous Substack dedicated to exploring the pragmatic literature of the German-speaking Middle Ages, shares his thoughts on historical language learning and a passion for the medieval world. Follow Robert’s journey learning historical forms of German against the backdrop of picturesque Marburg on the Lahn, and the techniques that Robert used to maximize his language study. Robert’s story may inspire you to add Old High German, Middle Low or Middle High German to your polyglot agenda!

Robert, before we get into your language-learning journey, can you tell us what historical languages you read and why they’re important for your specific area of academic interest?

Like all university students of Medieval German literature, the bulk of my language study was in Middle High German, which I began during my Bachelor’s degree. However, I also read Middle Low German, and speak and read modern German.

My main academic interests are in the High Middle Ages and the dawning Late Middle Ages in the fourteenth century. My specific field is very narrow and neglected: administrative and legal books of Middle Low German-language Hanseatic cities. These books are not only in Middle Low German as well as Latin, but also in medieval legalese.

I wrote my Master’s thesis about a famous but yet-to-be researched 1299 Latin and Middle Low German-language legal book, the cartulary of the Hanseatic City Lübeck: Lübeck Stadtarchiv Hs. 753. (You can read more about cartularies in this Substack post of mine.)

This manuscript is considered pragmatic Hanseatic Literature, that is literature which originates from among the informal association of trading cities along waterways in Northern Europe, especially along the Baltic, known as the Hanseatic League. The manuscript is fascinating because it contains a mixture of Latin and Middle Low German, a city chronicle and maritime law statutes, all which work to establish a hanseatic identity for Lübeck as the emerging League’s center. It is a book which was used day-to-day by the city administration, as can be seen in the many signs of usage like marginalia.

When I presented my Master’s thesis to the Modern Literature Institute, they were bewildered as to why the codex I researched should even be considered literature. There is more interest in these books in the Law Department than in the Literature Department. Still, some “pragmatic genres” do count as literature in the modern period too, such as correspondence between modern authors.

“What is pragmatic literature? It’s literature bound by purpose. It fulfills a social role. It seeks to hold a social order together. It demands your respect at the minimum and has some kind of legal authority at the most, which, even when perceived differently in the Middle Ages, still carries considerable weight. It helps to build a consensus of the communé, outside of which there is nothing legal or lawful in the medieval world.”

(Read more of Robert’s work on this subject here.)

What inspired you to study the Middle Ages?

I find the medieval urban culture of burghers interesting, while the first and second estates—clerics and knights—are more popular in medieval studies more generally. The urban culture of the High Middle Ages strikes a chord because the medieval city, beginning in the twelfth century, is really a beginning of Karl Popper’s “free and open society” (as are, further back, the Ancient Greeks and Hebrews).

Citizenship in a medieval city meant having no allegiance to a lord, as well as enjoying the medieval version of freedom. Clerics and nobles were forbidden property ownership in a city, whereas craftsmen and especially merchants became wealthy property owners who administered their own law. While not exactly democracies, medieval cities provided citizens with a kind of personal sovereignty and a possible way out of serfdom. Merchants were on an eye-to-eye level with bishops, dukes and kings. Sometimes they were even more influential and had the upper hand owing to the wealth they generated.

As I reflect further on this question, I suppose my interest may go even further back. As a kid, reading J.R.R. Tolkien over and over, I was fascinated with the Middle Ages, literature and languages as well. As a medieval philologist, Tolkien studied the Germanic languages beyond Old English, including Old and Middle High German, as well as Old Norse and Old Icelandic. He obviously drew on these to create his fantastical languages and stories.

What are some of the difficulties that a prospective learner of Middle High German might encounter?

There are considerable grammatical differences between Middle High German and modern German which must be mastered to understand texts. For example, the “future tense” is built, or rather implied differently (it doesn’t actually exist). The genitive case is used copiously and in forms unknown of in modern German. There are double negatives like niht nihtes—not nothing—which are similar to negations in American slang along the lines of, “I didn’t say nothing,” which does not mean, “I said something,” as logic suggests. The equivalent of “not a whit” is a Middle High German idiom, ni-wiht, which did not survive into modern German.

Middle High German is a foreign language for native German speakers, too. Understanding words and their nuances requires some history and cultural context. “False friends” are perilous as they are in many languages. For example, Hochzeit in modern German means “wedding,” but hochzît in Middle High German is any festivity, literally “high time,” while wedding is brûtlouf, literally “bride walk”—a word which does not exist in modern German. Without looking it up, one can’t assume an unknown yet familiar-appearing word means what one thinks it means.

And you speak modern German fluently as well? How did you become so proficient in Germanic languages, historical and living?

I first learned German as an American Field Service (AFS) exchange student in Hamburg, Germany. AFS was founded in the wake of World War I to promote international understanding and peace. In Germany, I lived with a host family consisting of university professors. My host mother had herself been an AFS exchange student to the United States.

At sixteen years of age, I soaked up the language, attending a preparatory “high school,” or Gymnasium, for a year, and found myself becoming fluent fairly quickly. Immersion is really the only way to acquire a foreign language. One needs to leave one’s native tongue behind for a while and forget it. I always avoided English speakers and Germans trying out their English in Germany for this reason.

In my host family, their grandmother, Babu, spoke the Hamburg Plattdeutsch dialect—a modern form of Low German—so I was exposed to what was becoming a dead language at the time. “Low” refers to the low country in the North and its dialect is much closer to English than is High German. For this reason, Low German can be more intuitive as a native English speaker than it is for a High German native speaker. For example, the word for “bottle” is buddel, not Flasche.

Plattdeutsch is enjoying a comeback now, particularly with young people. Harry Potter has even been translated into Plattdeutsch, so, it’s not really a dead language, but is instead seeing a revival.

In 2017, I went back to university in Marburg, Germany, to finish my Bachelor’s degree, which I had left unfinished at UT Austin when I decided to study music at the Ali Akbar College in San Rafael, California. At Philipps University Marburg, I completed a Master’s degree in German Literature specializing in the Middle Ages and Medieval Philology in 2023.

The Philipps University Marburg was a great place to study. It is one of three university towns in Germany where the town is the university. It’s small, so there are few distractions and, unlike Hamburg, it was not bombed out during World War II, so it retains its medieval charm. As my advisor’s assistant, I had a little (shared) office with a view of the E-Kirche or St. Elisabeth Cathedral—the oldest Gothic cathedral east of the Rhine (pictured below).

For a small university, Marburg has one of the biggest Medieval German Literature programs, next to the Humboldt University Berlin, Munich and Freiburg, which are larger institutions and have just as much going on “in the Middle Ages,” so to speak. This was my advisor’s joke to new students of Medieval Literature first arriving to the seminar: Willkommen im Mittelalter (Welcome to the Middle Ages).

Outside of your immersive cultural experiences in Germany, how have you built vocabulary and proficiency with modern German?

I owe much of my advanced German vocabulary to my avid reading of Thomas Mann. This is the stuff of the Bildungsbürgertum—the educated bourgeoisie of the outgoing nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

You can’t separate language from culture. Goethe and Schiller are indispensable and have impacted modern German culture so much. You hear references to Faust all the time, even in advertisements, and Germans can quote from Goethe’s famous play without ever having read it or even knowing what they are quoting from. It’s a little like Shakespeare coining countless turns of phrase which have become standard English.

The other area that I consider vital is philosophy. When I began studying it at UT Austin, I had a brilliant professor there, Louis Mackey, who introduced me to medieval philosophy: Augustine, Aquinas, Anselm and Avicenna. Since then, I have read most of the canonical philosophers, especially Aristotle. Although I was eventually drawn away from philosophy, its study is useful for developing critical thinking skills and learning to build arguments.

Are there any pedagogical differences between language study in Germany when compared to the United States, for example?

In German education, learning happens mainly through independent study, not in seminars. Students are expected to be proactive and to come up with their own assignments and exercises. Professors don’t hold your hand, there are no mid-term exams, attendance is optional. This is probably very different from what North American students expect and, in theory, one could never attend class in Germany and still pass with a passing exam. The final exam mainly consists of a research paper, which is also different in Germany. Unlike anglophone essays, a German research paper reads like an unembellished list of facts; its style is “standardized,” rather than individualized. Readers of my Substack posts may see that I lean towards this dry style, although I do make an effort to include the essayistic!

What was one of the first texts that you translated independently? Do you recall anything about the challenges in approaching that text?

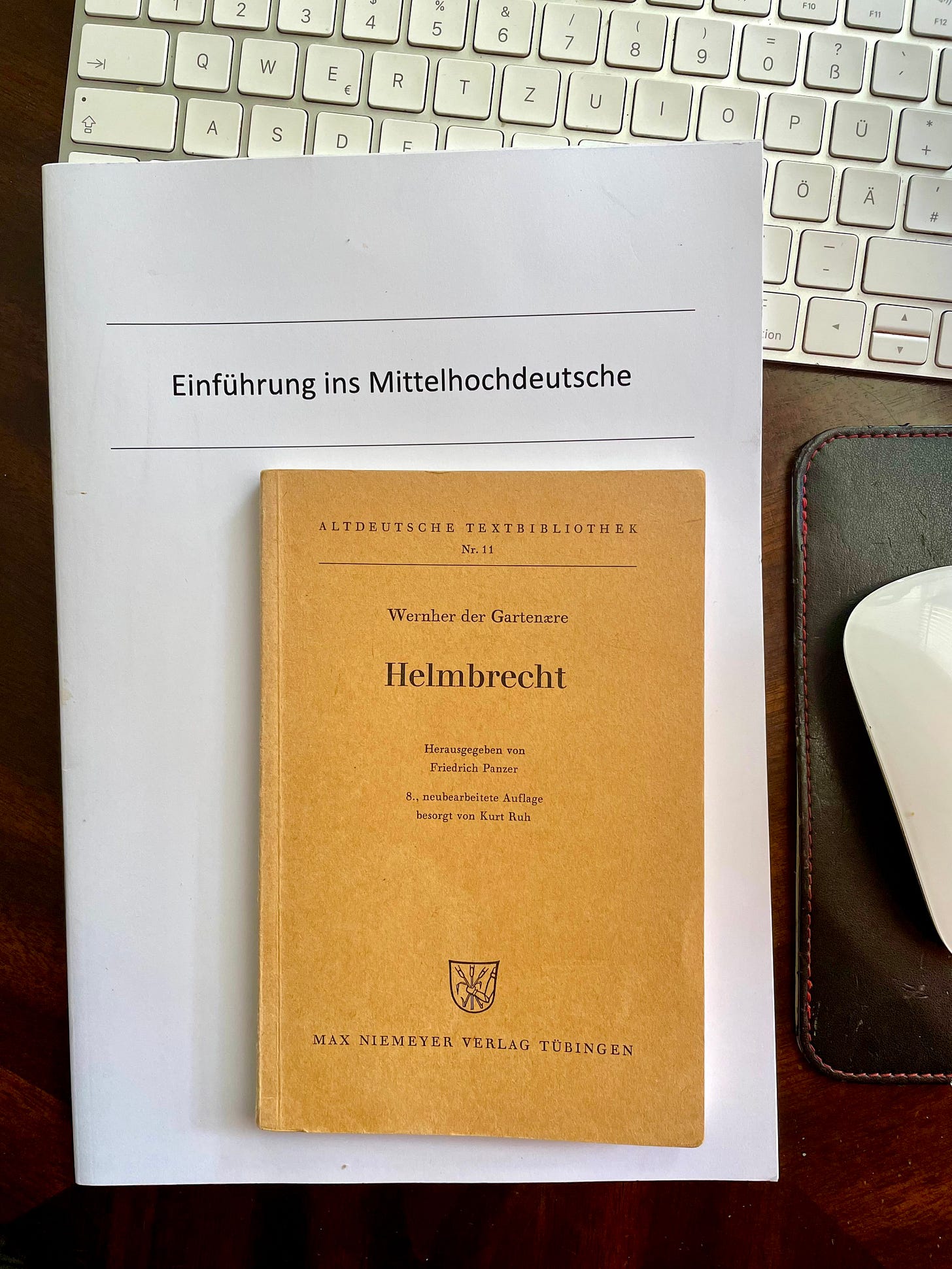

In the Introduction to Middle High German seminar, my advisor always teaches a little-known text, Helmbrecht by Wernher der Gartenære—a thirteenth-century medieval epic poem. One reason my advisor chooses this text is that there are no translations into modern German to “cheat” from. Students translated a certain number of verses each week to discuss in class. The exercise was not to “get it right” but to get closer to the text by learning from one’s mistakes and misunderstandings.

Wernher’s story also serves as an introduction to medieval courtly German Literature in a way, because the harlequin figure, Helmbrecht, a serf, wears a hood onto which images from the great epics are embroidered as an attempt to insinuate himself into courtly society and attain upward mobility. This is seen as an upset to the social order. Helmbrecht feigns having command over the current courtly literature, a status symbol he only portends to.

Figurative poetry from a foreign time and place presents certain challenges. For example, I recall a description of Helmbrecht’s long hair which he wore from his shoulders hin ze tal—“down to the valley.” Here, Wernher paints a picture of Helmbrecht’s long hair flowing from his head as though from a mountain, as far as it can go, but the clever simile is unexpected.

Poetry is a daunting form, but is a staple of the Middle Ages. Because spelling is far from standardized and dialects are always in play, looking up a questionable word can turn into a scavenger hunt for the writer’s intended meaning. Often, one can only pick the most likely candidate and rule others out. Taking the context into consideration is crucial when deciphering such elusive passages.

What textbooks or texts did you begin learning your target languages with?

In the introductory seminar, we used a short self-published grammar by a professor at the Philology Institute, Christa Bertelsmeier-Kierst, as well as the standard grammars by Bergmann, Weddige and Hennings. The grammar lessons were introduced through examples in the medieval texts we read, thereby reducing dependency on the textbooks.

“…I always memorized words and their forms parallel to reading original texts since abstract grammar charts seem best leveraged by advanced students to double-check things, rather than a paradigm to be committed to memory in the absence of a primary text.”

What has been most beneficial to you in learning various historical German dialects?

Looking back at the syllabus, my advisor, Herr Wolf, called it finding “the way through the sentence.” This involved identifying the verbs first and making sentence diagrams to orient oneself in it. As one typically learns medieval languages to read and understand texts, not necessarily to write original compositions, certain language activities, such as learning verb conjugations, are more passive.

As for what helped me most, in contrast to students who prefer rote memorization via flashcards, I always memorized words and their forms parallel to reading original texts since abstract grammar charts seem best leveraged by advanced students to double-check things, rather than a paradigm to be committed to memory in the absence of a primary text.

Additionally, I can’t recommend reading enough. Reading, reading slowly, reading the same passage over and over and reading aloud are the most productive things to do, besides learning grammar, which should be learned in tandem with the texts and not in a vacuum of charts and tables. Learning to use resources like dictionaries, which are complicated, and other digital tools is also important. For example, the platform, Middle High German Term Database allows one to search for variants of a word in the literature so you can find concrete examples of a word’s use.

Oddly enough, another thing that helped me with language learning is music. I studied the classical music of India, which comes from an oral tradition. This involved a lot of memorization because scores are not read, as in the Western, written tradition; rather, one learns directly from one’s teacher. Music demands a lot of practice, discipline and patience, which language learning also requires. Music is also a kind of language in itself. I still practice music daily and find it a great personal resource.

Finally, I recommend memorizing poems and reciting them. This exercise used to belong to primary education in the past.

Where would you objectively rate your proficiency with the languages now? Are you actively continuing to learn them, or more passively immersed in them through translation?

I am able to read a Middle High German classic while rarely consulting a dictionary (maybe every few pages). I can enjoy it like I would a modern novel. The classics define standard vocabulary, because they are the works the creators of the dictionaries used. The vocabulary of obscure texts can be more challenging.

Old High German is another matter as it goes much more slowly for me and requires more looking up in dictionaries. I never concentrated on it.

Reading entire translations in modern German is mostly useless and even irritating for me. The beauty and poetry of the language as well as the cultural nuance gets lost. Sometimes they are, however, useful for checking things I am unsure of.

Translating medieval German bits into English for my Substack posts has been an experimental and new experience. It is exciting, because some of the pragmatic texts are not even translated into modern German. English translations of classics are available, but I have not looked into them. I have translated some from modern German to English for academic articles by my advisor and other professors in the Department to be published in English language anthologies, like an article about Merlin in Old Dutch and Old Flemish Arthurian literature (pp. 194-203).

Robert, for readers unfamiliar with your Substack, what led you to the platform and what do you write about?

I started posting on Substack as a way to stay engaged with the subject matter that I’m so passionate about and to stop the bleeding of forgetfulness. I recently started reading a classic—Tristan by Gottfried von Strasbourg—and began by examining manuscript digitalizations. I was so inspired by my early research that I decided to write about it for English speakers as an experiment really.

I take an introductory approach to the German-speaking Middle Ages as they are less well-known in the anglophone world, but, at the same time, my Substack assumes certain “medieval basics,” like an understanding that books were handwritten by scribes before Gutenberg, for example.

The Middle Ages are “international” because Latin is the universal official cultural and religious language and Latin-speaking elites operated “internationally.” When the vernacular is used, it is an outlier. Nations as we know them had yet to exist and so, a work like Beowulf is as relevant to German Medieval Studies as Hildebrandslied is to English Medieval Studies, in my opinion.

I translate bits of content into English on my Substack. When I do this, I am mostly taking directly from a manuscript, not an edition. Older editors especially took unimaginable liberties with original texts, sometimes almost assuming the role of “co-author”! Alternatively, they cherry-picked from several manuscripts as it suited them, arbitrarily creating a mishmash which never existed and then called it an authoritative text. When digitalizations are widely available, it is essential to read from quality images of medieval manuscripts independently from the editions, or at least in parallel.

“The more time you consistently spend in the Middle Ages, the better.”

Finally, if you could offer any advice to someone considering embarking on the study of these languages, what would it be?

This is a tough question. The main thing is to be passionate about it, but this is not something developed from hearing advice. Having curiosity is a prerequisite, as is the ability to ask the right questions. Immersion is undeniably a challenge with dead languages, but not because of a lack of learning resources. While curiosity is a sin contrasted with humility during the Middle Ages, we are not medieval people. Every other advantage one might have will not make up for a lack of curiosity, in my opinion. Patience, on the other hand, is something no one is born with and which must be nurtured. It is obviously very much needed when learning languages, especially in the beginning when it is slow going. Accept that this is the case and that “two steps forward, one step back” is the order of the day. Enjoy the process. Know you are going over the same passages again tomorrow before tackling the next one. Repetition not only trains your memory but keeps you immersed in the text. The more time you consistently spend in the Middle Ages, the better.

This looks like a great interview! I can’t wait to read it later 🥰