Digging Deeper: Finding Layers of Meaning in Translation

Some thoughts on "slow language learning"

I’m a bit of a hoarder when it comes to language learning: books, articles, notes, notebooks and any other loose-leaf surface on which you could make a notation. Yes, even the backs of receipts (don’t ask). As I commented to someone in my chat recently, I wish my approach had the sleek, organized look of YouTube language learners who make lovely segmented sections in notebooks dotted with various colours, but instead my storage solutions are plastic tubs and my notebooks bear a striking resemblance to the Charlie Day Conspiracy Wall.

From one perspective, it’s a fascinating documentary journey. I can take the bulky steno pads I used in my earliest Latin classes and see indecision in every scribble. Ablative or dative? Accusative singular or genitive plural? The tentative approaches at deduction coupled with copious marginal notes show the struggles of an early-stage learner. Years later, it’s nice to see how far I’ve come, no longer needing my stash of multicoloured hi-liters to attack passages in the bulk of the translating that I now do day to day. Can I pick up Macrobius and consume it with the ease of an airport paperback? Nope, that’s still out of reach, though I’m comforted to know that the revered Mary Beard probably can’t sight-read it either!

I began learning Old English after Latin. My research trajectory made it clear that I could no longer rely solely on secondary translations, especially since I wanted to understand the subjects I was researching better, the notations they were making and the glosses they were adding to Latin texts. Thankfully, I had learned a few things from my first journey with one “dead” language, including the necessity of bringing life to it through various forms of linguistic production.

When I began to study Old English, I vowed that I would do things differently. First, I had decided that I would largely do it on my own. Although I did wind up taking a self-paced introductory course, I was in the middle of thesis research, taking an advanced Latin readings class and caring for a parent going through a health issue; the idea of putting additional pressure on myself in the form of a live grammar-translation class just seemed too much at the time.

However, I knew what had given me issues when learning Latin. Aside from my first formal class being an intensive summer bootcamp and thus perhaps not the true measure of more reasonably paced classroom instruction, when the time pressure was taken out of the equation, I knew my brain needed repeated exposure to grammatical concepts and the opportunity to work through them in situ. The “lab-grown” environments of Wheelock or Keller and Russell’s companion exercise books, while seemingly helpful for drilling concepts, often fell apart for me when seeing those constructions in their natural habitats.

I also needed to take things slower given how much was on my plate. Inspired by the peace and mindfulness of slow living, I was determined to take things at a snail’s pace, digging in and digging deep, being mindful about what I was reading, reading texts aloud and querying every construct with the spirit of a beginner even if I could accurately pick a case out of a line-up. Perhaps most importantly I vowed not to put pressure on myself—not to plough through a chapter a day or to assume I should be able to read some unadapted text within a few short months. My brain simply wasn’t up to the challenge.

Ugh…Grammar!

In an article I recently read on the realities of lexical size in Latin, the authors made an interesting comment about the way grammar is taught. Contrary to the more extreme side of the CI camp which sometimes de-emphasizes grammar to excess, the authors indicated that while the ratio of time spent on grammar instruction may be inflated, ultimately what grammar concepts are taught and why should be put under the microscope.1

“If we want students to develop sophisticated and accurate mental representations of Latin, explicit grammatical instruction is probably useful mostly to promote ‘noticing’ of grammatical phenomena in texts that students are reading. Otherwise such instruction may have its benefits…but it probably won’t increase reading abilities.”2

(Tom Keeline and Tyler Kirby, 2023)

The authors, Keely and Kirby, made an interesting point: grammar instruction doesn’t necessarily increase reading ability. But is that entirely true? This point can be argued ad nauseam. Vocabulary or grammar—what’s more important? As uninspired as this answer may be, I think it’s ultimately both.

Vocabulary alone will not help you understand what’s happening in a sentence. Lurking on Latin-language message boards, I often see autodidacts using LLPSI without a companion grammar text post that they don’t understand why “in via” became “in viam”—a subtle but significant distinction between place and motion. For this reason alone, as efficacious as CI may be in achieving spaced repetition, it cannot be a practical or exclusive substitute for the “drier side” of language study.

In thinking about shifting grammar instruction, my early approach to Old English grammar was all about dissecting a text. While I volley back and forth between the perils of over-reliance on parsing versus learning to read a text, I did find it helpful in my early OE journey. Instead of trying to tackle every primary text under the sun to achieve mass input with only a cursory understanding of what I was reading, I decided I would unpack every inch of a text, even if it meant that I would spend up to a week or even more on a single excerpt. I vowed to tackle each noun and verb with care, each sentence as a unit, query syntax and note grammatical rules and then ask myself what each sentence was saying before trying to turn around and restate it with what limited vocabulary I already had. This went beyond parsing: it meant researching, writing and internalizing a text on multiple levels.

A Different(?) Take on the Grammar-Translation Method

With my mind slightly overwhelmed at the time, I didn’t have the mental bandwidth or emotional fortitude I had with Latin to spend countless hours copying out paradigms (though I still maintain it has a useful place in language learning). I was so scattered that even when I tried to memorize something as basic as pronouns or internalize the function of the prefix to-, I felt like there was an impenetrable mental wall precluding any retention.

At that point, I embarked on my “slow” approach. I had already worked through a gentle introductory text, Drout’s Quick and Easy Old English, and most of a self-paced course. I understood weak and strong declensions at a high-level, had a general grasp on verb forms and conjugations and I understood the cases. Wulfstan’s Institutes of Polity was by no means within reach, but simple Bible passages were and perhaps a little of Ælfric’s Grammar.

I began working with the passages from Marckwardt and Rosier’s Old English Langauge and Literature, mostly because I found that, out of the various grammar books I had checked out of the library to compare and contrast their content, I liked its set-up best. They also had a fairly manageable assortment of short, mostly glossed texts, and since my goal was depth not breadth, it seemed the most functional.

“It is of great importance to obtain a clear idea of the province of grammar as opposed to that of the dictionary.” (Henry Sweet)

Forþan þe stæcræft is seo cæg…

Henry Sweet, covered in a previous post, has been a useful resource in my OE journey. Despite more recent scholarship on the science of language acquisition, good old Hank still has a few gems of wisdom that we would do well to contemplate.

The biggest challenge of any language can be grasping the meaning of a word, sentence or larger text. Latin learners are often told to tackle complex sentences by locating the verbs and bracketing off sections of a sentence for easier translation. However, in this approach—and I have been actively working to reprogram my mind—we never really learn to read, to take words as they come, to hold the complexities of the language in our minds, and to infer meaning sequentially. Yes, this hunt-and-parse method has enabled me to translate texts, but it hasn’t necessarily made me the best reader. Translation and reading are two different beasts.

Sweet argued that “grammar…is merely a commentary on the facts of language.”3 In learning it, one needs to see unambiguous examples, alongside words and syntax. In his view, learning bare lists of words is “the greatest blunder.” Although, I disagree insofar as our minds make connections in many ways and sometimes that’s through encountering an interesting word (and, of course, I need to justify my recurring Anglo-Latin Words of the Day), we ultimately have to grasp the entirety of what’s going on in a text in order to understand it holistically.

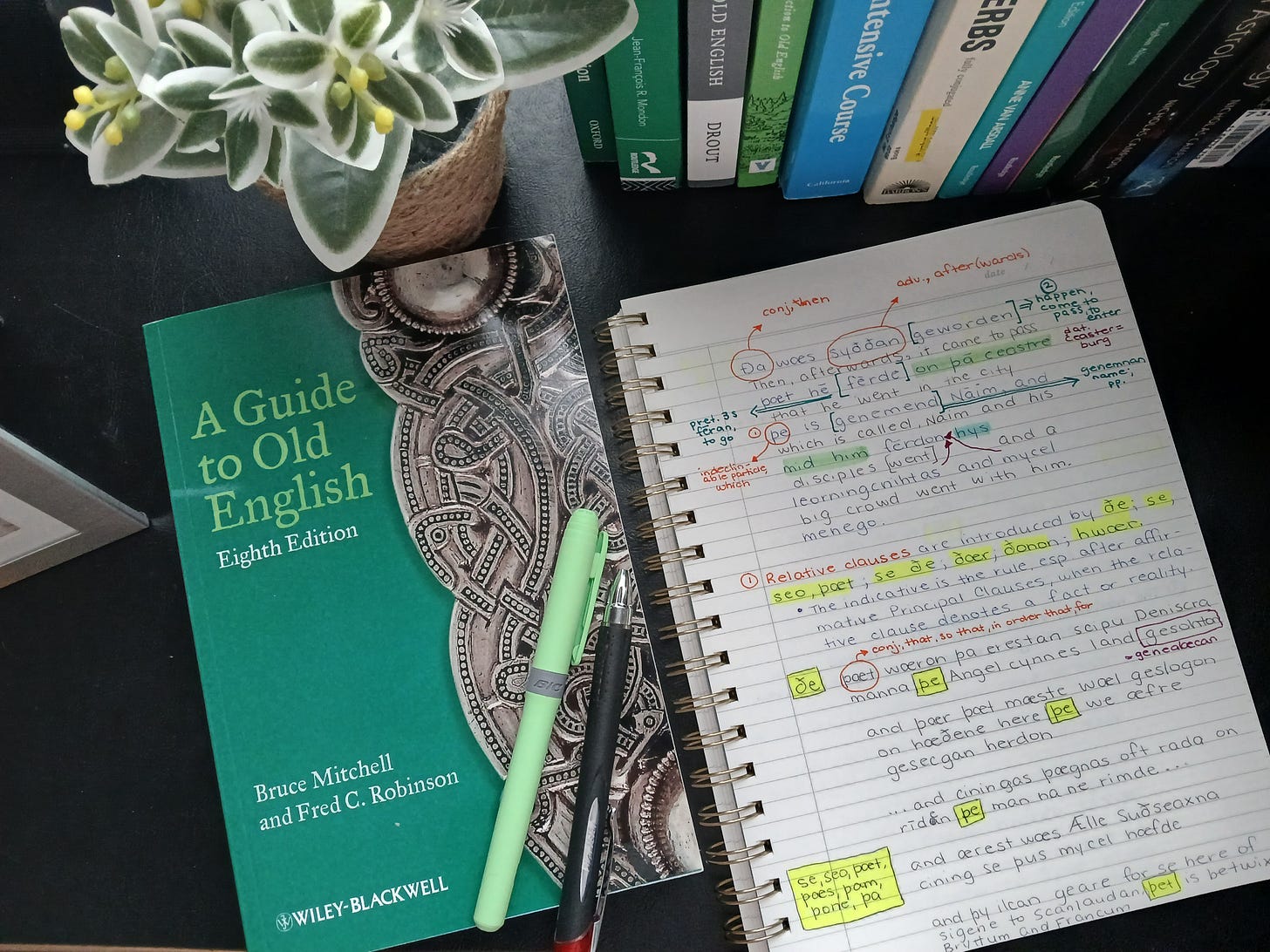

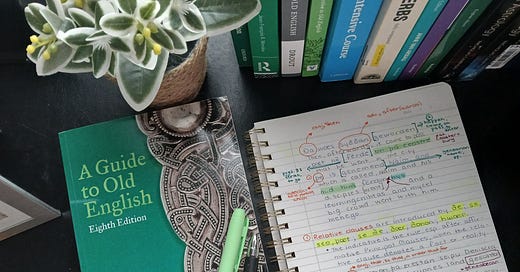

In the above-pictured example from the Gospel of Luke taken from one of my OE notebooks, I worked with a single sentence at a time. The excerpt in Marckwardt and Rosier was around a page long, but I probably spent a day or two on no more than two or three sentences. In going line by line, I was careful to unpack everything I came across, taking little for granted. I relied on studies of Old English syntax freely available on the Internet Archive to supplement grammatical discussions in the textbook. The indeclinable particle “þe” may only get a passing mention in a textbook as one way that reflexivity can be expressed in a sentence, but as it appeared throughout the excerpt, I made it a point to understand not only how it might be used in this context, but also other ways of expressing the same construct. I copied out examples from books on OE syntax by hand, supplementing the textbook’s discussion.

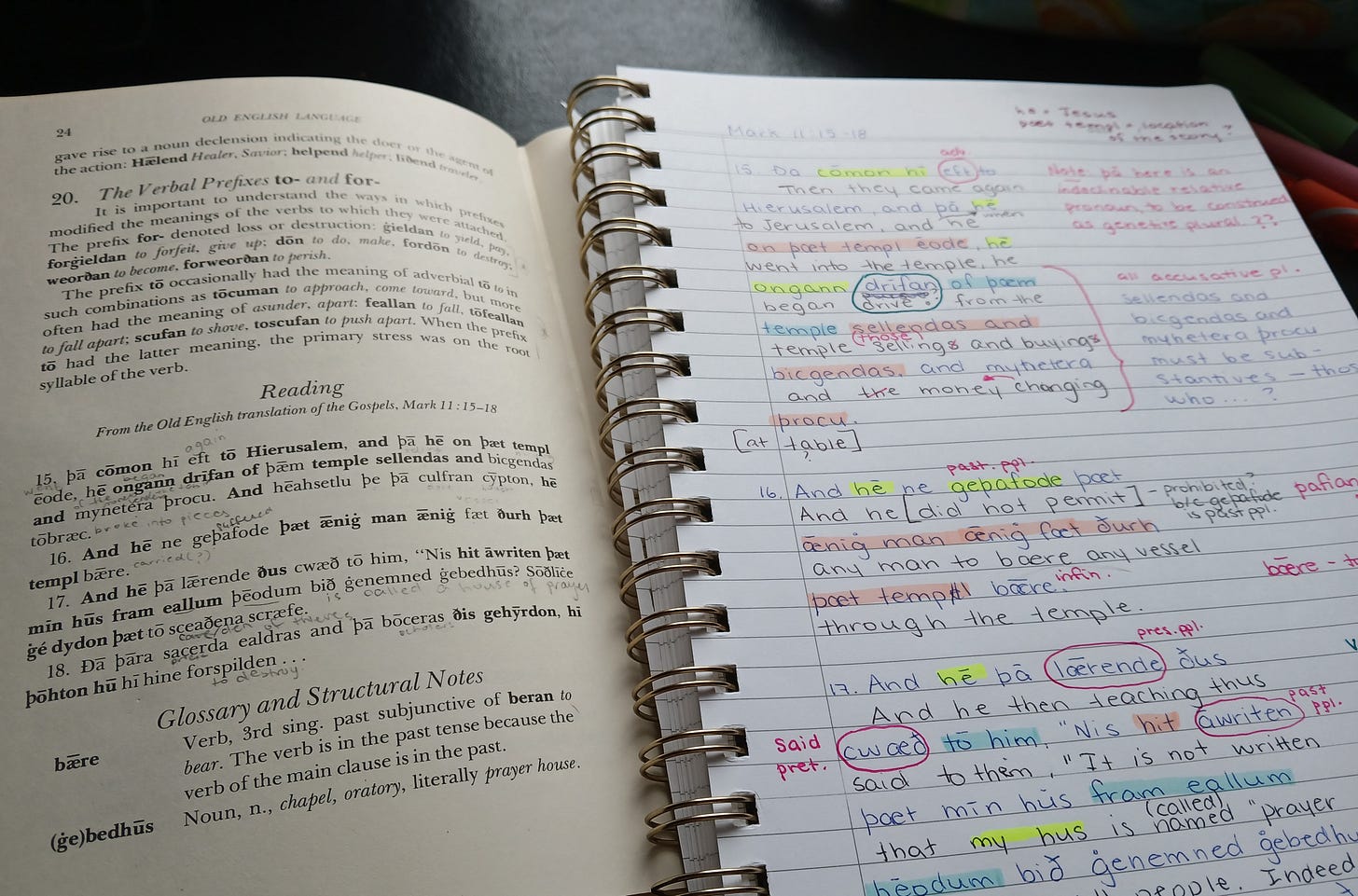

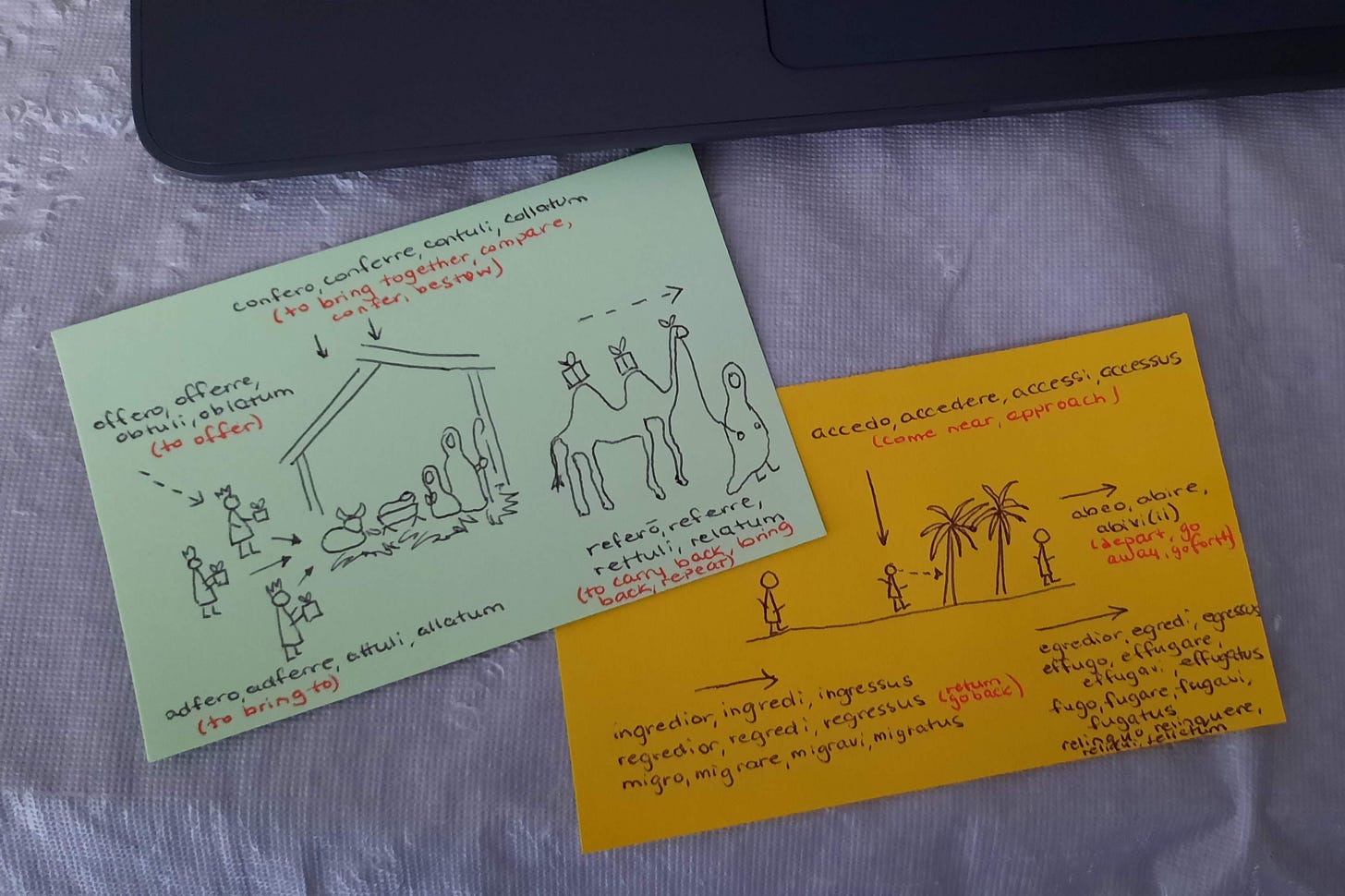

In my slow approach, each noun got declined, each verb conjugated—perhaps not with the same repetitive zeal that I had been determined to drill it into my head with Latin, but slowly, methodically and with deliberation. Verb prefixes were studied because they themselves are their own microunits of meaning. Where possible, I tried to find synonyms for words. Prepositions and cases were identified where necessary and I even tried to query certain word combinations to understand if phrases that seemed clumsy in my Modern English translation might be better rendered idiomatically and if those idiomatic constructions existed. In another picture below taken from the Gospel of Mark, you’ll see a struggle with substantives; I knew the Modern English story, but had to understand how it had been rendered into Old English so as not to slip carelessly into a quick translation. Feeling artistic, I sometimes drew pictures and labelled them, adding visual cues to new vocabulary.

After all this was done and copious notes created, I then translated my Modern translation back into Old English, testing my recall. Did I remember that “siþþan” could mean “afterwards” but also “since”? Had I internalized the third-person past indicative form of “fēran”? If not, I created lists of problem words and reviewed them over the course of successive days. I recited the sentences with my horrible pronunciation not because I had any intention of reciting the Gospel story in any public setting, but because language is ultimately an oral phenomenon—it has a rhythm, a sound, a flow. And it’s a story-telling device. The spell in godspell—the Old English word for Gospel—can, on its own, mean a narrative, a story, a telling, a remark or even a sentence. It is both a unit and a totality. That was how I had to understand a text.

Finally—and I argue this is where the real magic happened—I created my own sentences. Awful sentences. Basic sentences. Sentences that would be no more sophisticated than those a four-year-old might speak playing in the fields of tenth-century Wintanċeaster. However, language production is essential and often gets overlooked in the grammar-translation approach sometimes taken in learning classical languages or even older forms of our own modern vernacular.

While we may want to dispute vehemently Ælfric’s assertion that the grammar is the key, it is certainly a key to grasping meaning. In fact, as Sweet argued perhaps a bit hyperbolically, though his point is well-taken: “the whole of language is an incessant struggle and compromise between meaning and pure form, through all the stages of vagueness, ambiguity, and utter meaninglessness.”4 If we follow Sweet’s logic, then, as he helpfully points out, grammatical concepts are tools for description and need to be studied alongside text: adjectives denote something’s permanent quality or attribute, adverbs an attribute of an attribute, and a verb their changing attributes or phenomena, and together we start to understand what a sentence is trying to convey.5

Did I Grasp the Meaning?

After the meandering journey and seemingly excavatory explorations into a single word, sentence and paragraph, you may wonder whether I grasped the meaning any better, and the answer would be a middling, “sort of.” For all the scholarship that aims to deconstruct, decry and reconstruct the grammar-translation method, or that argues for spaced repetition, lexical immersion, and other strategies for acquiring facility with language, I do think that there really is no hack, tip, or trick. However, I also think that grammar is not, as Keely and Kirby suggested, to be more narrowly circumscribed or treated incidentally.

In a way, the two go hand-in-hand. Perhaps this is not revelatory, but maybe, in a way, redemptive of the older methodologies. When you know the form of a word and its function in a sentence, even if you don’t know the word per se, a dictionary can help you clear the issue up in an instant; it can’t help you do the opposite.

This slow approach did, however, help me with successive texts and more conscious recognition. It allowed me to continue with the text, as I frequently went to Benjamin Thorpe’s edition of the Gospels and worked through the balance of the text. When I filed the reading away to cycle back into the rotation at one, four, eight, and twenty-four-week intervals, I was confident that most, if not all of its words would, at a minimum, be stored somewhere deep in my brain box.

Tips for “Slow” Analysis

If you wanted to try this approach, then here are a few suggestions. First, assemble your tools: for me, some paper and an assortment of coloured pens or hi-lighters. Notecards are useful for vocabulary and doodles, but by no means essential.

Then you need a few books and textbooks: you can use your favourite ones, but don’t underestimate the older tomes on the Internet Archive. There’s something to be said about the seemingly antiquated approaches taken by textbooks a century ago. For Latin I always like Allen and Greenough (helpfully digitized through Dickinson College), but don’t forget the books specially dedicated to syntax. I would argue that even when we can parse a sentence accurately, sometimes we still can’t make heads or tails of it, even if we can correctly identify each constituent element. For Old English, a text like Samuel Ogden Andrews’s Old English Style and Syntax, or for Latin E.C. Woodcock’s A New Latin Syntax were particularly helpful, but there are no shortage of such texts and you can find ones that address the nuances of what you are searching for.

Then, in my view, you’re ready to begin.

Read the text in full more than once and read it out loud. The point is to go slow and see if you can glean anything on your first, second or third pass. This is the opportunity to jot down a few observations. Perhaps you might note the principal players? In the example from the Gospel of Luke 7:11-21, maybe you recognize that there is someone called Iohannes, you might note that a “sunu” is also here—a son—and someone called “se Hǣlend.” Maybe you recognize “hǣlend” as an agentive noun owing to its suffix? Perhaps you don’t know the verb “hǣlan” yet, but, at least you’re in for a three-for when you do: once you know the meaning of the infinitive, you’ll easily know the present participle as an intermediary step between the verb and the agentive noun.

Scan for any words you know, but only with 100% certainty. Sometimes we can get caught up with trying to make translations fit ideas we instantly have about a text. It’s important that we don’t assume we know anything or think we recognize something. When in doubt, it’s best to skip it and confirm it in the process of your deep analysis, but if you know beyond a shadow of a doubt that “mildheortness” means “compassion,” then by all means jot it down wherever you prefer—on the text itself, or below it if you’re working with a skipped-line notebook transcription format.

Parse the text. At this point, you may be ready to shift into your more detailed analysis having exhausted everything you observe about a text. This is where your focus moves to taking a sentence at a time. Establish colours for your cases—nominative, accusative, genitive and dative in Old English; Latin will require an extra colour for the ablative. Historically, I have not colour-coded the vocative as it isn’t that ubiquitous, but you may be working with a text that contains an invocation in which case you may want to identify it separately. Colour-code your sentence according to the cases; identify adjectives, adverbs, verbs, auxiliaries, pronouns, conjunctions, particles and so on.

Note any potential syntactical features of the language. Here, I am particularly thinking about special constructions beyond a direct, simple sentence—things that may require a little extra consideration to render into English. This may be idiomatic translations of auxiliaries, correlative conjunctions or anything else that needs a little extra thought beyond the straightforward word-translation approach. Sentences beginning with “Đa” abound in the Gospels and the Chronicle, so it may not be a bad idea to use this opportunity to dip into a bit of syntax to understand how it might be rendered best in Modern English.

Itemize relevant forms. If there are multiple verb forms, list them—did you see participles, the present indicative, the preterite form? What were the endings you observed? What about nouns? Did you see accusative and dative plurals, singular forms? Note them all down separately since you can use this to practice forming these on your own later, especially if you struggled to recognize an ending.

Use the language. This step is a little catch-all, but an important one and largely depends on how you learn best, how much time you want to devote to this exercise and (potentially) how good your art skills are. (j/k) The aim of this step is language production, not simply identification or translation. Once you’ve translated the entire passage, you have myriad options for practicing the vocabulary and syntax learned by trying to retell your passage in very simple words you know, a combination of your primary language and target language, image-telling stories and any other approach you can conceive of. However you slice it, as long as you’re forming something in your target language, you’re doing this step right. Perhaps you learned that “se Hǣlend” was another word for the Saviour, or Jesus, and you know that “hǣlende” means “healing” and you learned that “meniġu” means a multitude of people or a crowd. That’s enough to form a simple phrase (though perhaps not a complete sentence): se Hǣlend meniġu hǣlende. The point is, you know that you needed a subject and you formed a present participle and you may have even gone and looked up the declension of “meniġu” and found that it remains unchanged in the singular, only taking a separate genitive and dative plural ending. Suffice to say, the point is that you’re using the language, interpreting it, quizzing yourself, considering forms and ultimately trying to produce your own new creation from what you know about the features of the language at this stage.

Translate your final English translation back into your target language. On a separate page, copy your English translation out in the manner that you prefer (as separate blocked sentences or as skipped lines), and translate as much as you can back into your target language. I found that it’s best to do this a day or two removed from your translation efforts just to ensure you’ve let sufficient time elapse so as to really activate that grey matter. I wasn’t too much of a stickler for a grammatically or syntactically correct translation at this point. Sometimes, I didn’t know how to decline a word, though I knew I needed it to be in the accusative plural or the dative singular, so I would simply write the noun I knew in the nominative and noted the form that it needed to take. This could help form the basis of later study sessions. The point was simply evaluating how much I had retained.

File it away for a while. There’s a fine line between work and overwork and certainly we measure progress by learning new forms while building on old content. Once you feel like you’ve sufficiently worked the text (by this point you might feel like you’ve stuck it into a blender and made it into an indistinguishable mush in your brain), you should leave it be. Put it into the laundry hamper because you’ll give your mind a good mental rinse and cycle this text back into your reading arsenal at a later date. You can choose the interval, but I usually glanced at it periodically within one to four weeks of translating it. Then, I put it away to cycle back six months later.

Hopefully, this has given you a few ideas you can adapt for your own language-learning journey, or even taken some of the pressure off our more regimented, progress-focused approaches. At a minimum, I just wanted to offer another pathway to my more disciplined January language-learning post, showing that you can, indeed, take multiple routes to gaining increased proficiency with a language.

Tom Keeline and Tyler Kirby, “Latin Vocabulary and Reading Latin: Challenges and Opportunities,” TAPA, 153.2 (2023), pp. 531-559 (p. 550).

Ibid., pp. 550-551.

Henry Sweet, “Practical Study of Language,” in The Collected Papers of Henry Sweet, ed. by H.C. Wyld (Oxford: Clarendon, 1913), pp. 34-55 (p. 41).

Sweet, “Words, Logic, and Grammar,” in The Collected Papers, pp.1 -33 (p. 16).

Sweet, “Word, Logic, and Grammar,” pp. 17, 19.

Your "slow learning" approach is brilliant. I've really enjoyed reading how you thoughtfully apply so many concepts of Second Language Acquisition/Applied Linguistics. You've found the best way for you to meaningful engage with the language and deeply master the meaning and form. I'm inspired by your work-ethic...I find I'm constantly trying to balance taking enough notes with keeping it "fun" and "light." When I get too ambitious, I burn out. Thanks so much for sharing!

This was beautiful, thank you! I absolutely agree with you. There are so many different ways to learn a language these days, and to settle or focus on only one, is to do a great disservice to your language learning over time. I wrote a whole thesis about this, and I felt as if I only scratched the surface. It was about Latin pedagogy over the last 2000 years, and it focused on some of these issues, between the "grammar" school and the "spoken Latin" school. I'll be writing my own story of teaching myself Latin over the years sooner than later, but I've found many of things you point out here to be true for me as well. Although I'm a big fan of speaking Latin, and I speak it a little myself, I also see how it can be used as a crutch where no one is learning grammar, or, it's an extremely slow process, especially for an adult. Furthermore, trying to find the "perfect" method is also a fool's errand, because so many of us learn differently, and who's to say if it worked for me it will automatically work for you? I've had the same experience, working in Lingua Latina, desperately trying to "stay in the target language" and then eventually saying, "screw it, I'm going to an English dictionary!" It's not a sin to fall back on your native language. If the greatest Latinist of all time (Erasmus) did so, then so shall I! I've come to discover, there's often not a lot of nuance to these arguments.

I say, take your time, find something that works for you, and go at it one day at a time. Language learning should be enjoyable, not torture.

Thanks again!