How the Glossing Tradition in Anglo-Latin Texts Can Help Us Learn Languages

Learning languages with interlinear and marginal glosses.

With the conversion to Christianity, monastic and priestly training became paramount in Early Medieval England. Once competent in the recitation of the Scriptures and the performance of various Latin rites and rituals, these individuals would be entrusted with the all-important cura animarum.

To facilitate learning, glossing Latin texts became one method for aiding would-be English oblates in acquiring proficiency in the language of their new religion. But can the “glossing tradition” help present-day learners of historic languages? This month’s language-learning post is dedicated to asking this very question.

In contrast to the Tolkienites and the Beowulf-stans, I came to Old English to read magical and divinatory texts. At the time, my research was predominantly focused on the corpus of text-based tools known as “prognostics”: onomantic devices, schedules for bloodletting according to the lunar cycle, birth predictions based on Scripture, lists of inauspicious days, and dietary prescriptions dictated by the heliacal rising and setting of the “Dog Star,” Sirius.

For the most part, these texts have been unevenly translated. Some found their way into Thomas Oswald Cockayne’s nineteenth-century Leechdoms, Wortcunning and Starcraft of Early England, a few were peppered throughout Robert Thomas Hampson’s Medii ævi Kalendarium, but until Roy Liuzza published his translation of prognostics contained in London, BL, Cotton MS Tiberius A iii, most modern-day researchers had access to poorly edited, imperfect, and fragmentary volumes of seemingly “orphan” texts. The only way to read prognostics, charms, and medical recipes reliably was to translate them yourself. (And, to an extent, this still remains true.)

While modern academics have taken aim at Cockayne’s subpar editorial standards, the sad reality is that most of the corpus of surviving texts in Old English remain untranslated. While we helpfully have modern editions of the Old English Herbarium, the Old English Boethius, and other “great hits” in the linguistic predecessor to our modern vernacular, more obscure texts that don’t fit neatly within the canon of Old English literature tend to get left by the wayside. Perhaps it’s not particularly glamorous to translate prayers or predictions, however, the extensive glossing that finds its way into many of the original manuscripts might be a powerful language-learning tool for those aiming to learn Latin and Old English.

What is “glossing”?

In the Anglo-Latin corpus, at its most basic level, glossing is the addition of the equivalent Old English word (or explanation) atop or in the margin next to the corresponding Latin one. By and large, there’s nothing particularly extraordinary about the interlinear or marginal glosses ubiquitous in these manuscripts as far as mechanics go. Scholars generally agree that glosses ultimately functioned as didactic tools central to Medieval learning. In England, the tradition may have had its origins with Theodore of Tarsus whose seventh-century school at Canterbury was regarded as a beacon of rigorous learning. Subjects as diverse as computus, astronomy, and even theoretical astrology may have been taught, but, as far as the ultimate religious education goes, elements of Latin grammar would have been paramount for English monks and nuns.

In the preface to his edition on the eleventh-century Vitellius Psalter, James L. Rosier observed that, with some exceptions, it was customary “to gloss [psalters] word for word without concern for syntax.” This was not exclusive to psalters, however, as Cotton MS Tiberius A iii demonstrates, with its extensive interlinear glossing of prognostics that inspired a previous post. This word-for-word construct is noteworthy insofar as we can extrapolate pedagogical approaches that may have privileged learning Latin in the order that it had been written, rather than translating the spirit of a line or phrase into Old English and rendering a syntactically correct version in the glossator’s native language. The aim may not necessarily be to understand the text in English, but rather to understand how it was constructed and patterned in Latin.

There is something special about glosses when regarded as portals into a historical moment. Countless cloistered Medieval men and women engaged in language learning, production and transmission, interpreting and reinterpreting myriad texts for the purposes of educating cadres of pupils in a foreign language that formed the basis of ritual and belief, but also higher learning. A glossator’s choices reveal temporal, oral, and dialectical uniqueness, further illustrating how fluid language was and will always be—a living, breathing organism at a point in time, not merely a static word on parchment. Scholars have also examined more complex roles that glossing could have played beyond the didactic: questions of power, authority, bias, and interpretation all come into play in the choices that glossators made. In later centuries, marginalia in cathedral schoolbooks show how pupils may have engaged with the subject matter they were studying thereby revealing stories needing to be told beyond the the original text itself. Though we are accepting glosses as purely linguistic devices for the purposes of learning historic languages, like every other extant text, glosses are products of complex social, cultural and religious moments. They are created by individual agents with their own particular motivations, perceptions, and worldviews.

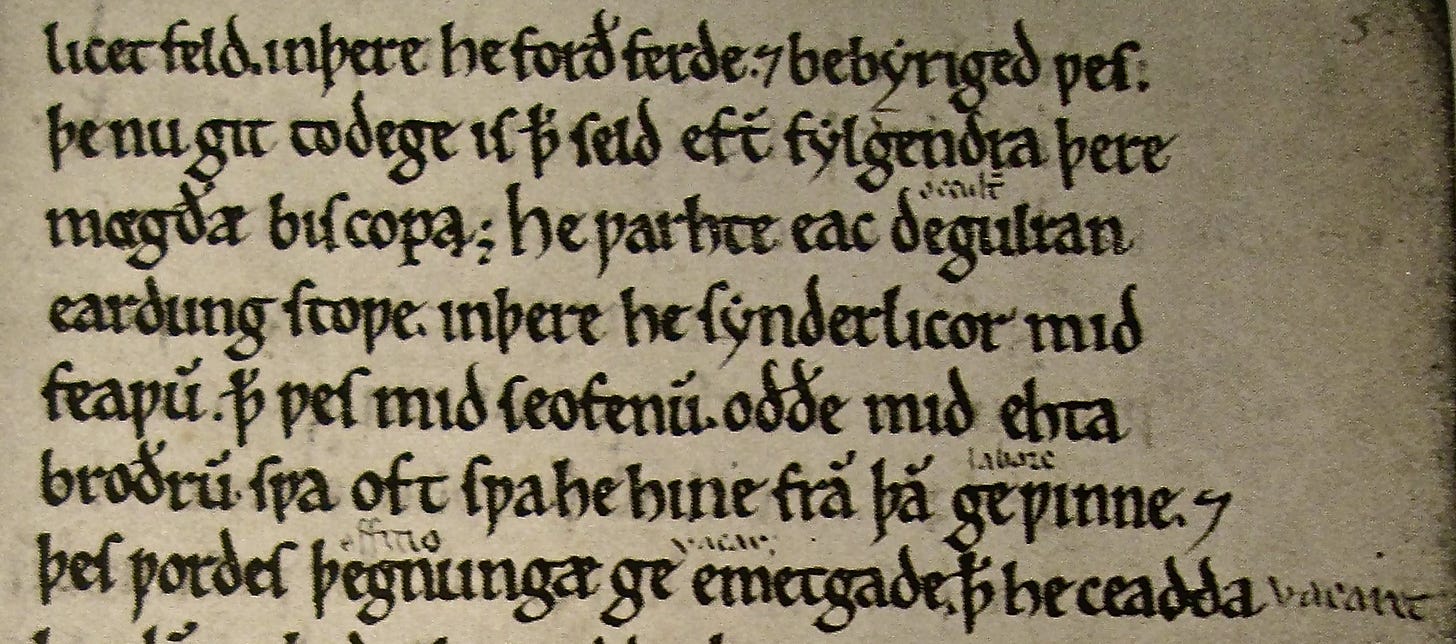

While the glossators of most manuscripts are unknown to us today, the visually stunning Lindisfarne Gospels, available to view on the British Library’s website, was famously glossed in the Northumbrian dialect by the Provost of Chester-le-Street, Aldred the Scribe (ca. 950-960). Aldred was known to have glossed several texts, some of which may be found today in the Durham Cathedral and Bodleian Libraries. We also know that Æthelwold, one of the architects of the tenth-century Benedictine Reform, did his fair share of glossing of psalters and prose texts, however, my favourite scribe remains the thirteenth-century “Tremulous Hand of Worcester.” The Tremulous Hand, as the name suggests, wrote with an evident shake in his script. Some manuscripts reflect a less perceptible tremor than others—the one excerpted below, for example, does not demonstrate the magnitude of the tremor that the script could take on, with some glosses revealing a considerable lack of steadiness. He has been identified as a scribe in almost two-dozen manuscripts, glossing thousands of words; his annotations of various medical entries have led historians to speculate as to what medical condition he suffered from, showing that glossing provides many keys to the past beyond simply language transmission.

Ultimately, it may seem reductive to suggest that glosses first and foremost helped readers understand a text, but, let’s face it, Early Medieval English monks and nuns were among the original SLA (“second-language acquisition”) scholars, promoting their own form of comprehensible input. Whether Bede, Ecgbert, Byrhterth, Ælfric Bata or Hild, all men and women committed to leading a religious life, had to learn Latin.

Can glosses help you learn historic languages?

To some extent, if you’ve picked up a copy of Lingua Latina Per Se Illustrata, the Cambridge Latin Course, Colin Gorrie’s Osweald Beara, or even Le Français par la Méthode Nature, then you’ve already experienced a modern-day version of glossing. Some of the worksheets that I make available monthly tend to have various marginal glosses to help practice translation. This approach is not particularly novel, nor is it the exclusive domain of Medieval texts. Glossing remains a modern language-learning tool, though a consistently running interlinear gloss is more of a rarity.

From my experience, using glossed manuscripts and even edited print volumes of various Anglo-Latin codices helped with my Old English acquisition on a couple of levels. First, it saved time. Instead of looking up each word in a dictionary, I simply glanced at the Latin word that the Old English one was glossing to understand what I was reading. While one might argue that this only partly aids in Old English acquisition as the interlinear glosses are not reordered according to proper Old English syntax, in my earliest stages, it was nonetheless helpful to see vocabulary declined and conjugated, even if it followed the structure of the Latin language rather than the Old English one.

A second benefit of using glosses was the contextual specificity it offered. Taking an example from some old research notes, I would have been left scratching my head if a glossed birth lunary—that is, a set of predictions made about the future of infants according to the days of the lunar month—was all I had at my disposal. In MS Tiberius A iii, the phrase “‘wiðerweard letted he bið” glossed the Latin, “aduersus impeditor erit.” In his translation of the prognostics in this manuscript, Liuzza (whose work I hold in the highest esteem) rendered ‘letted’ as ‘lette[n]d’ and interpreted it as a noun meaning “hindrance,” thus translating “wiðerweard” as the subject of the sentence and “lette[n]d” as part of its predicate: “Misfortune will be a hindrance.” This breaks with the formula established by the birth lunary predictions where, structurally, each entry without fail maintains the infant as the subject of the prediction. Thus, interpreting the gloss as an extension of the Latin, it was (and remains) my contention that a case can be made for interpreting “lette[n]d” as a masculine agent noun, derived from a verb and the agentive suffix -end, much like Scieppend (creator) is derived from the verb scieppan (to create) + -end, or timbrend (builder) from the verb timbran (to build) + end. This more closely aligns the Latin “adversus” with the Old English “wiðerweard” and “impeditor” with “lette[n]d” while simultaneously preserving the consistent structure of the predictive format.

As the above demonstrates, glosses can be clues, helping us to deduce meaning. Glossators made conscious choices about the synonyms they used, helping to illustrate how ideas were likely rendered and interpreted in Old English. Often when we open a dictionary, we are confronted with more than one word for the same concept. Which one do we choose? All synonyms are not created equal. Take two Old English words for child: bearn and cild. Without a contextual note, we might not immediately appreciate that bearn was typically reserved for someone’s child—a named, identifiable offspring—whereas cild refers to a child more generally. If time-travelling, an eleventh-century Rochesterian might get the gist of you discussing any children that belonged to you if you mistakenly called them your cildra, but you’d certainly be a twenty-first century standout since you really want to refer to a named son or daughter as your bearn. This phenomenon is particularly helpful when learning Old English from its Latin glossing: you witness the careful choices made when translating languages and have the opportunity to query and investigate those choices for your own edification.

Now, not everyone has a handle on their Caroline Minuscule or Insular Majuscule, so many Medieval manuscripts, while digitally accessible, might as well be written in Greek. Similarly, not every Old English learner comes to the language after or even with Latin in their sights. This is not a problem. There are countless interlinear glosses edited and reprinted by modern scholars (I’ve identified a few below), which I maintain can be used independent of the Latin being glossed. The point is that glosses can act as a kind of dual-language text and effectively be placed in the hands of the autodidact as a powerful pathway to language acquisition.

However, the benefits of glossed texts should not be overstated. One study by Frank Boers suggested that glosses may not necessarily be the most effective tool when “learners ‘passively’ take in the information and then carry on reading without giving further thought to the glossed item.” Boers maintained that language students achieve better learning outcomes with new words when glosses are treated as study tools—a point well worth heeding when approaching any type of glossed text. As adult learners, we likely bring more sophisticated reasoning strategies to bear on any text we work with, noting other linguistic features, like case, gender, and number, and so we might already be better-positioned to make the most of glossed texts.

Glossed texts also differ from bilingual texts insofar as translator “influence” is largely absent. Instead of making conscious decisions how to render a phrase into intelligible Modern English, glosses strip the text bare, so to speak, focusing only on the equivalency of the words and minimizing the “artistry” of translation. When I polled subscribers in my chat around the use of dual-language texts, opinions were mixed. Some regarded the quality of translations as unhelpful when not faithful to the letter of the original, while others noted the various linguistic liberties taken by translators. I certainly share this perspective—bilingual editions of the Vulgate or Psalms often render the Latin into grammatically correct English, sometimes departing quite significantly from the original Latin. This may be one area where glossed texts could have a leg up on their competition.

Creating Your Own Glossed Texts

In a way, we’re glossing our own texts constantly when we write the definition of words between the lines or make marginal notes about grammar or syntax. Perhaps that’s enough when it comes to active engagement with a text, but can we take Boers’ advice around engaging with glossed texts a step further? Can we use the practices of Medieval glossators to better understand the natural flow and structure of our target language?

One benefit of glossing a text yourself rather than translating it is breaking the habit of treating your target language as a puzzle that needs solving. I’m particularly guilty of this when reading Latin, jumping around a sentence to render its components into intelligible English. However, we can surmise that Romans took in the words in the order that they appeared and glossing can help us do the same.

When creating an interlinear gloss of a text in your target language, the goal isn’t to reorder a sentence into comprehensible Modern English, the goal is to put yourself in the shoes of a monastic glossator, glossing a short Latin or Old English text with merely the correct word and grammatical form. In a way, you may get a better handle on the various structures you often read about in a language textbook. Recall all those sections in Old English grammar books that compare and contrast the SVO with the SOV word order? Glossing may be one way to internalize these and other patterns first hand. Take for example:

We cildra biddaþ þe þæt þu tæce us sprecan Lædene…

If we were to create our own interlinear gloss, then we would likely see a more familiar word order approaching our Modern English:

We children ask you that you might teach us to speak Latin…

Alternatively, we might gloss:

Circulos et enim sperae nouimus x esse.

The orbits and indeed of the sphere we know X to be.

In the latter example, the gloss is less easily intelligible based on our modern English word order. To make it intelligible, we employ all our rules of Latin syntax, rearranging post-positive particles, finite verbs, and so forth, until we render a sentence that approaches something that we might speak aloud today. However, what we miss in doing that is growing accustomed to the patterning and variations of our target language: the recognition of where the subject, verb and object may land in relation to each other, their relationship to adverbs and conjunctions, and even where the finite and infinitive forms of verbs are placed.

While I’ve been touting the benefits of interlinear glossed texts, I will note that they can be aesthetically overwhelming, at least for me. Perhaps I’m still too wedded to my analog ways, but if I can’t print the page out and cover the text being glossed, I do find myself occasionally distracted by so many languages and formats at once. For this reason, if experimenting with glossed texts intrigues you, then I would recommend finding a manageable system—one that not only enhances your ability to engage with the original text, but also promotes “active engagement.” This may take the form of writing out vocabulary you do not know on the covering page, or pausing to check the declension of a particular noun—either way, making the most of glossed texts should not involve speeding through at pace without contemplating the language. After all, in many instances, glosses are not to be treated as discrete, standalone texts.

For those Gaga About Glosses Dizzy for Dual-Language Texts…

The Internet Archive remains one of the most accessible places to seek out Latin and Old English interlinear glosses. Although not exhaustive, if experimenting with glossed texts intrigue you, then a few starting points could include James L. Rosier’s edition of the Psalms in the Vitellius Psalter (London, BL, Cotton MS Vitellius E XVIII), an interlinear gloss of the Tiberius Psalter or an interlinear gloss of Old English hymns. The hymns could make for particularly compact study sessions, as might the Rule of St. Benedict from this interlinear Old English/Latin edition or Æthelwold’s version. (By the way,

has a wonderful weekly translation and commentary on the Rule that readers may enjoy!)For those that want to stick with Modern English, then Benjamin Thorpe’s translation of Ælfric’s Catholic homilies are available for free on Wikisource and provide a clean view of the original Old English and Thorpe’s translation on the right. No, this isn’t an interlinear gloss, but it is still useful to add for toggling between Old and Modern English.

Latin learners may enjoy any of the above in addition to Johann Amos Comenius’ Orbis Pictus, which offers Modern English glosses of the Latin text in an easily digestible format. (I did want to link to another Substack that mentioned this text a while back, but can’t remember the author or the publication, so I do apologize as I like to cross-reference postings! If it was your blog and you’re reading this, let me know so I can update this and link to your piece!)

If high-brow classical Latin literature is your thing, then try this interlinear version of the first book of Ovid’s Metamorphoses or this glossing of Livy. Tacitus’s Agricola and Germania is also available in Modern English interlinear gloss in this compact edition for those seeking a riveting read.

Finally, the Bible can make for manageable intermediate Latin reading practice, and this mammoth 4,000-page rendering might be just what you need as you work through the translation on your own.

Interested in more meditations on learning (historical) languages? Check out some of my other posts:

Stuck in the Middle: Why being an intermediate language-learner sucks and what you can do about it!

Digging Deeper: Finding Layers of Meaning in Translation. Some thoughts on "slow language learning"

New Year, New Language? Five Tips to Ignite Your Language Learning Goals in 2025

Have you used interlinear glosses in your language study? If so, drop your comments below and let the community know your experiences with them!

Bibliography:

Boers, Frank, “Glossing and Vocabulary Learning,” Language Teaching 55 (2022), pp. 1-23.

Brown, Michelle P., “‘A Good Woman’s Son’: Aspects of Aldred’s Agenda in Glossing the Lindisfarne Gospel,” in The Old English Gloss to the Lindisfarne Gospels: Language, Author and Context, ed. by Julia Fernandez Cuesta and Sara M. Pons-Sanz (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2016), pp. 13-36.

Sauer, Hans, “Glosses, Glossaries, and the Dictionaries in the Medieval Period,” in The Oxford History of English Lexicography, ed., by A. P. Cowie (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), I: General Purpose Dictionaries, pp. 17-40.

Thorpe, Deborah E., and Jane E. Alty, “What Type of Tremor Did the Medieval ‘Tremulous Hand of Worcester’ Have?” Brain: A Journal of Neurology 138 (2015), pp. 3123-3127.

Great post! I'm currently in the thick of trying to figure out what to make of some glosses, so it's nice to see someone with more experience do a clear piece like this.

Thanks for the mention!